via Creative Commons I bet we've all experienced at least one of the following: (1) Being told we don't "belong" to a group we think we belong to. (2) Having someone assume we're part of a group with which we don't actually identify. (3) Hearing someone else identify with a group to which we belong, and being annoyed because we don't consider them a part of the group. Where does identity "policing" come from? And why, in the LGBTQ community,* of all places, does it seem to happen so often? I was pondering this the other day and came up with a short list of possible (no doubt interrelated, and no doubt often subconscious) reasons:

As I've talked about before, I'm no fan of identity policing. Nonetheless, I can understand the impetus behind it, and I bet I've unintentionally engaged in it. I hope I've caught myself, questioned myself, and asked where the impulse was coming from. Of course, identity policing and boundary-drawing doesn't just happen in the queer community. It happens with regard to age, race, class, and just about every other social group we can think of. Nor do I mean to suggest that identity policing always arises from bad motives, or the intention to exclude others. I suspect we'd all agree that it's important to have social and psychological spaces where we can understand ourselves, question our assumptions, and feel at home with people we believe are like us. What do you think about all of this? Have you ever seen, experienced, or engaged in identity policing? Do you think it exists in the queer community? Looking forward to hearing your thoughts.** * I was recently a guest speaker in a queer studies class in which several of the students suggested that calling LGBTQ folks a "community" is false and s ** If you feel the urge to write, "Why do we have to label ourselves at all?" or "We're all human beings," or something similar, please read this first.

13 Comments

This is a guest post by BW reader Jack Kaulfus, who also blogs at www.jackkaulfus.com and teaches writing in Austin, Texas:

I’m out there somewhere on the trans spectrum, socially and politically (by "trans," I mean one who self-identifies as transgender, transsexual, or gender variant). But I've always felt more inclined to identify myself as a woman--even if it means coming out to everybody in a 100 yard radius when the soccer referee insists that my coed team needs another woman on the field to continue the game. This past Tuesday, I was reduced to screaming "I'm a GIRL!" down the field after a short but excruciating "Who’s On First" set between my team captain and the ref. My name is Jack, so that complicates things further. Every time there is a public misgendering in which I am ultimately perceived as a woman, I sit in the middle of a heated exchange between the proud, transmasculine-identified me (TM) and the proud, queer woman-identified me (QM). The internal dialogue goes something like this: TM: You’re passing! Awesome. But you aren't really a girl, so you just kind of lied. QW: That was embarrassing. No one else has to prove she belongs on the field. Maybe you should start a fight. TM: Well, what did you expect? You have a low voice and a bit of facial hair. The other girls have ponytails. People don’t like to be confused. QW: F**k other people’s confusion. You don’t have to have a ponytail to be a woman. You’re not trying to deceive anybody. TM: BTW, studly, this particular binding/uniform shirt combo is really working for you tonight. QW: You need to talk to that ref after the game--educate her about how to deal with situations like these. You need to explain that policing gender at a sporting event is insulting to every woman here. TM: It’s her job to make sure people follow the rules. One of which you’re probably breaking because you have more testosterone coursing through your system than some of the guys on the other team. You should transition all the way. Quit waffling. Take responsibility for your own identity. QW: Yeah. Assuming that mantle of white male privilege is going to be a terrible responsibility. Make sure you’re prepared for the raise in pay and automatic deference to your opinion... TM: Not all men are alike. You are not like other men. QW: Not all women are alike. You are not like other women. TM and QW: I’m glad there will be beer after this game. The next time the ref was down my way, she apologized. I was prepared to just let it go (like I always do), but then she added that everybody was calling me Jack, so she was confused. I told her that Jack is my name, and then the ball came barreling toward us. Conversation over. At times like these, authenticity feels like a tiresome luxury. I’m not quite prepared to give it up, but it requires living in a state of near-constant personal revelation. I find myself needing to be prepared to answer for my gender in the strangest places and situations. I’ve been told many times that it just doesn’t matter--or that it really only matters to me, because I think about it too much. Gender is a social construct. Gender is all in my head. If I could only get past this pesky gender hang-up and live freely as Just Jack, I’d be happier. But so often, identifying and embodying one easily recognizable gender identity becomes the reason other people feel they should treat me with respect: I’m a girl for my co-ed soccer team, a guy walking through a deserted parking garage, a trans writer who can write with authority about girlhood in America. I could really get behind the idea that it just "doesn’t matter" if I weren’t constantly being asked to make a decision about how my identity fits into the paradigm du jour. BW note: Thanks to Jack for this great article, as well as Guest Post #3. Read more of Jack's writing at www.jackkaulfus.com. If you're interested in writing a guest post for Butch Wonders, email me here. This is a guest post by BW reader Jack Kaulfus, who also blogs at www.jackkaulfus.com and teaches writing in Austin, Texas. In this post, Jack writes about the experience of passing--and not passing--as a Texan man.

I discovered the term "transgender" in the late ‘90s, and since then I have cultivated a complex, contentious relationship with my gender identity. I’m pretty visible as a butch woman, but over the past few years, I’ve been taking a low dose of testosterone in an effort to bring my physical body more in line with how I have always wanted to look. As of this writing, I don’t plan to ever fully transition to male, but walking this androgynous line has offered me perspective I never thought I’d experience. I am 35 and I live in Austin, Texas, where queerness is usually celebrated in the community at large. I’m lucky to be here where I can walk this line in relative safety, without excess fear of physical violence or verbal harassment. I should add that I’m white-skinned, educated, and from a middle class background. That has a lot to do with my relative safety as well, especially in the south. The places where I pass as male are typically the more dangerous places to be seen as queer--small towns and suburbs of bigger cities. I think I’m usually shunted into a default category of male because my hair is short, and I’m usually with my long-haired partner and her two kids. I’m always surprised when I pass for longer than a few seconds, but if I do, I am offered a tiny peek at what it might be like to walk the world as a white Texan guy with a pretty wife at his side. It’s very different from the way it feels to walk around as a visible queer with a pretty wife at her side. Here’s what I notice I get when I’m out in public, passing as a cisgendered male:

I don't pass every time, but I pass often enough to feel the absence of those small privileges when they are not extended. I have come to believe that walking around my life as a visible butch woman requires a certain resignation to public invisibility on the whole. I’m here, I’m queer, and you probably don’t want to a) sleep with me, b) invite me to play on your ultimate frisbee team, or c) flirt with me in hopes of a large tip. I am recognizable as a human form--not necessarily ignored--but I definitely don’t register the same way a white, straight, cisgendered male does. I don’t have a vested interest in becoming that which I am not, but poking around in places where I am comfortably welcomed and valued (either as a butch woman or as a cisgendered male) definitely heightens my awareness of the privileges I take for granted every day. BW note: You can read more of Jack's writing at www.jackkaulfus.com. If you're interested in writing a guest post for Butch Wonders, email me here. Here's a tough question I got from a reader the other day. I'll do my best to answer it, but I bet it'd be even more useful if others weighed in, too.

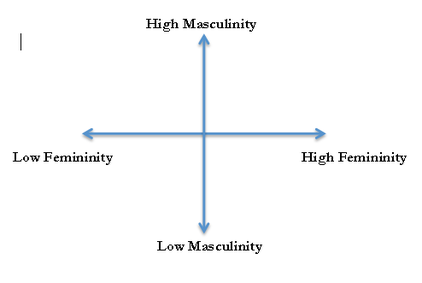

Dear BW, Can you do a post about how you know you're female even if you're gender non-conforming at some point in the future? I feel like an alien in a Halloween costume when wearing women's clothes, even if they're not overly feminine. I don't feel like a dude, but I don't feel like a woman either, as far as I can tell, but if you aren't into being girly, how do you know if you're a woman? My best friends are straight and I don't know how to talk to them about how they know they're women. I wear all men's clothes, and I really like getting called sir, but I think that's only because I get called miss maybe 70% of the time, and sir 30% of the time, and I like knowing I'm ambiguous. Thanks! C Dear C, First: good for you to have the courage to ask these kinds of hard questions about yourself! That's awesome. Second: I'll give you the best answer I can, but I can only speak from my own experience; you should definitely talk to as many people as you can. I had a conversation with my buddy C about something similar yesterday. We were talking about gendered pronouns (we both use female pronouns, but are often called "sir" and don't mind it), and I mentioned that if I was a kid today (I'm in my 30s), growing up in a progressive area of the country (which I didn't), I wondered if I'd have identified as trans. Why? Because I totally didn't fit in with the other girls. I didn't outgrow the "tomboy" thing--in fact, it became more pronounced as I got older. I wished desperately that I could wear a tux to prom instead of a dress (ugh). I can remember once in third grade, actually praying that God would come and turn me into a boy. I felt much more at home with boys than girls. Girls seemed foreign and hard to understand. Boys made sense, and played cool sports. (Mind you, I didn't feel like I was a boy, which many trans men report having felt.) For me, identifying a boy would have solved this particular conflict. But at the same time, I didn't feel uncomfortable in my own body (unless it was wearing women's clothes! I was like you, in that I preferred men's clothes even to non-girly women's clothes). It wasn't my body that was the problem--it was the culture around me (and the gender-based expectations and assumptions that culture contained) that were the problem. I thought my breasts were kind of inconvenient, but I never felt like they weren't "mine." As far as I can tell, this is a big difference between butches and trans men. (You might be interested in this post about why female-identified butches are different from trans men.) It wasn't until I started to meet butches and masculine women that I realized, "Oh! That's what I am!" Some days it would be nice not to get stared at in public, which I wouldn't if I was a man in the same haircut and clothing. But I don't feel like I "am" a man. I don't want to use the guys' bathroom. I like getting called "sir," as long as it doesn't happen all the time. It reminds me I'm different. Being a masculine woman just feels right to me. I don't feel alienated from my lady bits--especially not when they're under a shirt and tie. But put women's clothes on me and I'm suddenly an alien in my body. This tells me that it's clothes and culture that are the problem, not my gender identity. For my trans male friends, they didn't feel comfortable in their bodies no matter who they were with or what they were wearing. Even if they were alone in the shower, they felt as if they were in the wrong body. They hated being called "she" or ma'am. (I'm not saying this is the experience of all trans men, just of the ones with whom I've talked about this.) Until I was in my late 20s, all my best female friends were straight, and often fairly girly. Even when I was married to a man (that's a whole other story--here's a link to part 1 of that five-part story if you feel like reading it), I didn't feel like I fit in with the straight women. Now that I'm an out, proud, lesbian masculine butch woman, I feel like my straight female friends know I'm different from them, and respect it. I don't think they see me as less of a woman, just as a totally different kind of woman. And they often treat me more like a gay male buddy than like "one of the gals." This took some getting used to, but I actually like it now. The key point? Just because you don't conform to society's ideas (or straight people's ideas) of what "being a woman" means, doesn't mean you aren't a woman! I should also point out that a lot of people don't identify as male or female. Some identify as neither. Others identify as both. Some women get top surgery, because although they identify as women, they don't like having breasts. Some trans men keep their breasts, because they like them or their partner likes them or they can't afford surgery. There are all kinds of possible gender identifications and expressions. Although boxes like "male," "female," "butch," "trans man," "genderqueer," and so on work for lots of people, that doesn't mean they have to work for you. You can also pick more than one. You can also change whenever you want. There are no rules about gender, only patterns. You don't have to follow one that's already been laid out. I'm glad God didn't answer my third-grade prayer to be transformed into a boy. I love being a butch woman. There are hard things about it, yes, but overall, it just works for me. Keep questioning, experimenting, and looking for answers about your own identity, and I bet it'll become clear what works for you, too. Best, BW We hear sometimes that gender is a "spectrum." One reason to envision it this way is to see that gender is not dichotomous: It cannot be neatly divided into two parts like boys' shoes vs. girls' shoes in a department store. Most of us are not one or the other; we're somewhere in the middle: But even though the "spectrum" concept is useful, I've always found it troubling, because it understands masculinity and femininity as opposites. That means that if I'm deciding where I fall along the spectrum, I can't be more feminine without necessarily being less masculine--and vice versa. Here's what I mean: Culturally, we know what most people consider "masculine" or "feminine" (even though most of us probably don't agree with it!). Fixing my car is masculine. Painting my nails is feminine. (Again, I think these characterizations are awful, but I'm talking about culturally dominant notions of femininity and masculinity.) So if gender is a spectrum, and masculinity and femininity are opposite ends of a continuum, this means that if I paint my nails, I become less masculine. An act that moves me closer to the right end of the spectrum moves me farther from the left end. If the "spectrum" view is accurate, masculinity and femininity are a zero-sum game. But as I've been thinking about it lately, masculinity and femininity are more like a coordinate plane. (I suspect others have thought of this; I just haven't run into them yet.) Remember coordinate planes from high school geometry? Where you graph dots like (-1, 2)? Here's my version: The idea is that masculinity and femininity can be high or low, but are independent of one another. If you paint your nails, you become more feminine, but this does not necessarily make you less masculine.

For many of us in the queer/boi/stud/dyke/trans/butch/genderqueer realm, such a conceptualization might be more comfortable and accurate. Mentally, it disentangles the two ideas a bit. Imagine a hot femme changing her own oil--she's performing a culturally "masculine" activity, but is she any less feminine? I'd argue the answer is no, just as I'd argue that a butch cooing at a baby might be more "feminine" in that moment than she was a moment earlier, but that she is no less masculine for it. What do you think about this? Does it fit with how you think about gender? |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed